Part I: Exploring Identity with Founder Monisha Kapila

Part I of a two-part series on Exploring Identity with ProInspire’s Founder

Recently, I had the opportunity to join the Catalyst Collective, a community of practice hosted by ProInspire for senior leaders of color, at the inaugural group’s final convening. Members shared stories about how their identities and lived experiences shaped them and the work they were doing. I reflected back on how my early experiences have shaped me and what has guided me in my work at ProInspire.

My Formative Years

The first time I remember being aware of my identity was almost age 5. My Indian immigrant parents were eager for me to start Kindergarten at our local public elementary school in Flint, Michigan.

They took me for the entrance test thinking I would breeze through since I had already learned to read in preschool. During the test, the teacher showed pictures and asked me to say what they were. When she showed a picture of a milk carton, I said “doo doo” the Hindi term for milk that I had been using since birth. I failed the test and the school said I should return for kindergarten in another year. My parents were shocked and started to speak more English at home so a second language wouldn’t hold me back in school. When I came back to the elementary school a year later, they realized I was too advanced for kindergarten and skipped me to first grade.

I lived between two worlds – my “American” life which included friends from different racial groups in my school, and my “Indian” life which included other first-generation Indian immigrants.

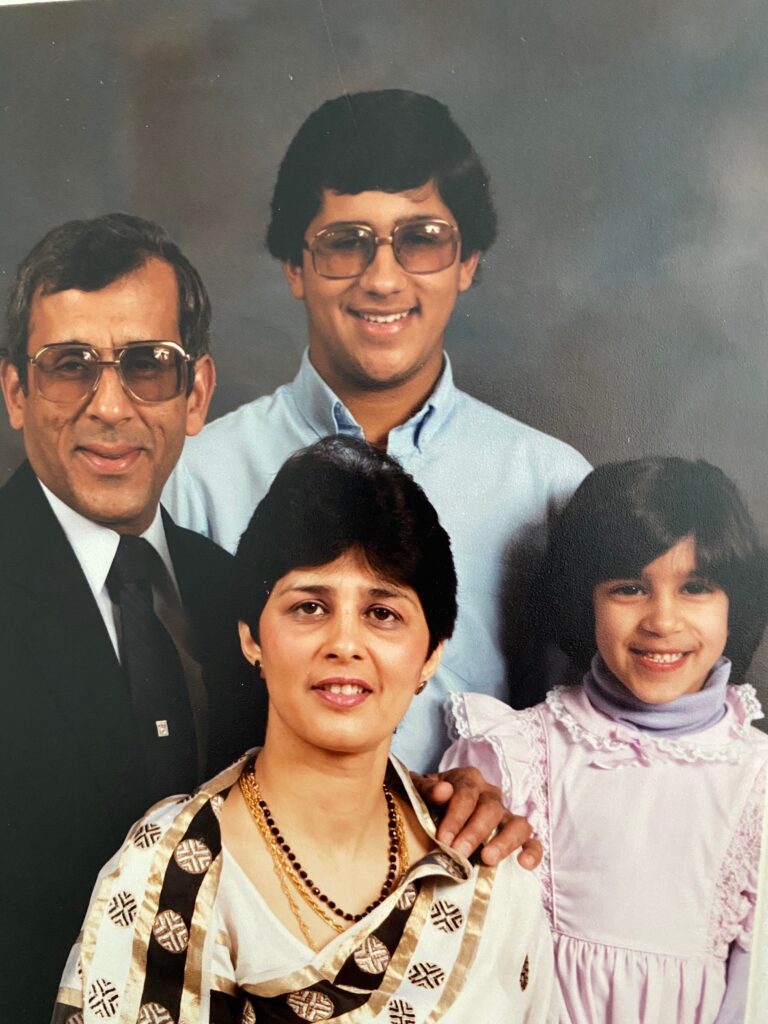

Through my school years, I was resistant to speaking Hindi and increased awareness for how my identity as a first-generation immigrant shaped my experience. I lived between two worlds – my “American” life which included friends from different racial groups in my school, and my “Indian” life which included other first-generation Indian immigrants. My parents had been raised in educated families in India, had strong English, and quickly adopted Western dress to fit in. I remember feeling pride that my parents were so Americanized that they didn’t wear saris to the grocery store. Still, I often felt different from my non-Indian friends and was frustrated when my parents didn’t support things like going to school dances or making Homecoming floats.

From a young age, my parents instilled values in me to make my community stronger. My mother’s father had been a freedom fighter in India’s fight against British colonialism. He served and lived at Sabarmati Ashram, which was home to Mahatma Gandhi. My father’s parents followed a reformed movement of Hinduism, Arya Samaj, that promoted civil rights, good deeds, and social reform.

My parents worked closely with Dr. Subba Raoji, a Gandhi follower from India, who traveled to the US each summer to share his message of peace and service. We had volunteer days where we would plant trees and take care of landscaping at the Hindu Temple of Flint. At age 14, I knew I wanted my peers to do more for our community and decided to sign up my high school for Operation Brush Up. Operation Brush Up was a service day focused on bringing together community members to improve houses in underinvested areas of Flint. I was able to get 30 of my high school’s students to participate in Operation Brush Up. That was when I realized I could be an organizer and leader to help improve our community.

When I went to college at the University of Michigan, I joined Project SERVE and helped organize the first Gandhi Day of Service, modeled after the MLK Day of Service. We had hundreds of students sign up to volunteer with a community organization as part of Gandhi Day. Living on campus helped me gain confidence in my identity as a South Asian American and my continued desire to be an active community member.

As I was preparing to graduate from college, I told my parents I wanted to work for a nonprofit and got the stereotypical immigrant response that “working for a charity is not a job”. They also reminded me that most nonprofits didn’t pay enough to entry level workers for me to live independently and they weren’t going to be able to financially support me.

I decided to take a job in the business world and joined Arthur Andersen. There I had great mentors, was continuously challenged, and received access to professional development. But every time an opportunity to do a pro bono project came up, I realized I wanted to be working on that and not on the big telecom projects I was assigned to.

18 months after starting my career, I had a wakeup call. My Mom, who had been battling stage IV breast cancer for five years, passed away.

I decided that I shouldn’t wait to do work that is more meaningful. I took a sabbatical and left to work for CARE International in India, using my business skills to help entrepreneurs in communities that had been devastated by earthquakes. Living and working in India also reconnected me to my ancestry. I remember walking around “Punjabi Bagh,” my grandmother’s neighborhood, and starting to understand the great cultural shift my parents had navigated. While I had felt that I lived between two worlds growing up, I realized how much harsher those different worlds must have been for my parents, who immigrated to the US in their 20s and only had their Indian networks to support them with that culture shift.

After 6 months of living and working in India, I returned to the US. I knew that I wanted to do something to support nonprofits to be stronger, but I wasn’t sure what was possible.

Launching ProInspire

The inspiration to start ProInspire came when I was working at Capital One. The company, like many other large corporations, had an internal university dedicated to supporting staff with skills and mindsets to be more effective. I thought about how all the nonprofits I worked for had done amazing work in the community, but there was no mechanism to support people inside the organization. I heard a presentation about the “nonprofit leadership deficit” and felt called to do something to support people who wanted to do work that created lasting change.

In 2009, I left my full-time job to launch ProInspire. This was an unknown path and not something that my Indian immigrant family would understand. But I had long taken a “non-traditional” path and they had confidence that I would figure out a way to make it happen. I had mentorship from other social entrepreneurs I met through service on a nonprofit board. I learned from their experience that nonprofit founders faced many challenges to building a sustainable organization. I also recognized that starting an organization without reliable income was a privilege unique at that moment in time – something only possible because I had minimal student debt, a severance package from corporate America, and a spouse with health benefits.

Like many people who start nonprofits, I was shaped by my lived experiences.

But I had learned from my time in the business world that I needed to have a “business case” for starting something new. So I talked to 120 people in the first six months of thinking about this idea. I identified a “market gap” – nonprofits wanted more diverse talent but didn’t know where to find them. Young people like me – who had not worked for nonprofits because of the “barriers to entry” – were interested in working for a nonprofit if they could find a job that paid decently and provided meaningful experience.

So I started ProInspire with a Fellowship to expand talent pipelines, recruit young business professionals, and address some of the structural barriers to entry in the sector. Our first class of Fellows was five young business professionals, all who identified as people of color. When I shared how my immigrant parents discouraged me from working in the nonprofit sector, they nodded their heads from having a similar experience. By sharing about my identities, it opened space for others to share their identities.

Many were the first in their family to attend college and knew that joining a nonprofit was a financial risk that impacted them and their families. Over the years, the ProInspire Fellowship expanded. We had amazing, diverse candidates for the fellowship and nonprofits always asked where we found these candidates. I knew the talent was there, they just weren’t looking for them.

While I got good at making my pitch for the “market gap” that ProInspire was filling, it took many years for me to share how my learnings were shaped my immigrant experience. I had to unlearn the idea that it was better not to highlight what made me different from the white norm, and instead learn that it was core to my authentic story. I also deepened my learning about structural racism and how the nonprofit sector came to be structured the way it was. The low pay for entry-level workers was part of how structural racism shaped the racial demographics of who worked in the nonprofit sector, and who held power in Board and leadership roles.

In August 2014, I was sitting around a conference table with the new cohort of ProInspire Fellows. We had 15 fellows in the DC fellowship that year, the majority of whom were people of color, and 9 identified as Black or African American. Earlier that month, Michael Brown had been fatally shot by Darren Wilson, a white police officer in Ferguson, MO, and I knew this would be important for us to discuss at our Fellows gathering. Fellows shared how Michael Brown’s killing had deeply affected them, and how they were personally participating in rallies and vigils. I asked who was at a nonprofit that was talking about how Michael Brown’s killing affected staff or connected to the work they did in communities, and not a single fellow raised their hand. I couldn’t believe that with all the organizations we were working with, many large, well-known, national organizations, not a single one had connected his killing to the structural racism connected to their day-to-day missions.

That was the moment that I realized that we needed to do more than focus on talent pipelines in the nonprofit sector…

Stay tuned for Part II of Exploring Identity with Founder Monisha Kapila

Learn more about the Core Commitment of Exploring Identity by downloading our Self to Systems: Leading for Race Equity Impact.